Initialement publié le 22 juillet 2023 @ 20h51

Par Michel Gurfinkiel

Le Conseil de Sécurité des Nations Unies a voté le 23 décembre 2016 une résolution (UNSC 2334) déclarant illégales toutes les mesures en termes d’aménagement du territoire, d’urbanisme, de peuplement ou de développement économique prises par Israël dans les territoires dont il a pris le contrôle à l’issue de la guerre des Six Jours.

Cette résolution, qui s’applique notamment à tous les quartiers de Jérusalem situés au-delà de la ligne de démarcation en vigueur jusqu’au 4 juin 1967 – « Jérusalem-Est », c’est à dire aux deux tiers de cette ville – a été adoptée par quatorze membres du Conseil de Sécurité sur quinze. Le quinzième membre du Conseil, les Etats-Unis, s’est abstenu. Quand des résolutions analogues avaient été présentées dans le passé, les Etats-Unis leur avaient opposé leur veto, ce qui annulait purement et simplement la démarche. Cette fois-ci, la résolution est valide.

Il y a lieu de penser que l’administration Donald John Trump, qui succédera l’administration Barack Hussein Obama le 20 janvier 2017, prendra des mesures pour empêcher l’exécution de la résolution UNSC 2334 ou pour imposer son abrogation. Si tel est le cas, le moyen le plus simple d’y parvenir est de contester non seulement la pertinence ou la légalité de cette résolution – qui, entre autres choses, viole et vide de son sens une résolution antérieure sur laquelle elle prétend s’appuyer, la résolution UNSC 242 du 22 novembre 1967 – , ou le fonctionnement actuel de l’Organisation des Nations Unies (ONU), de plus en plus aberrant au regard de sa Charte constitutive, mais bien la légalité de toute démarche contestant la légalité de la présence juive en Cisjordanie et à « Jérusalem-Est ».

La résolution UNSC 2334, comme la plupart des autres déclarations ou résolutions de l’ONU ou d’autres instances internationales prétendant mettre fin à « l’occupation israélienne » en Cisjordanie et à « Jérusalem-Est » et défendre « les droits du peuple palestinien », affirme de manière axiomatique qu’Israël n’est en l’occurrence que l’occupant militaire de territoires qui lui sont étrangers et sur lesquels il ne détient aucun autre droit. Or cette affirmation est fausse.

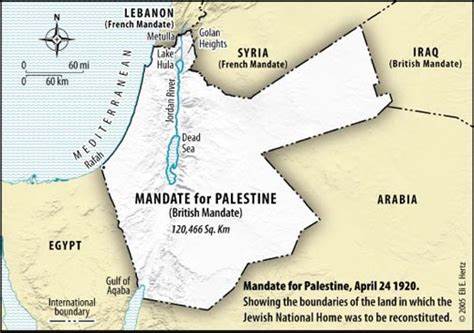

En effet, aux termes du droit international, la Cisjordanie et « Jérusalem-Est »appartiennent toujours, le 23 décembre 2016 à la Palestine, telle qu’elle a été créée par une déclaration des Grandes Puissances adoptée lors de la Conférence de San Remo, le 25 avril 1920, et par un mandat de la Société des Nations (SDN) adopté le 24 juillet 1922. Cette Palestine est explicitement décrite dans ces deux documents comme le Foyer National du peuple juif. Et l’Etat d’Israël en est depuis 1948 le seul successeur légal

Quelles qu’aient été alors les arrière-pensées stratégiques ou politiques des Britanniques, des autres Grandes Puissances et des membres de la Société des Nations (SDN), quelle qu’ait été par la suite leur attitude, la création sous leur égide d’une Palestine/Foyer national juif, et donc, à terme, d’un Etat d’Israël, est pleinement valide selon le droit international public. Et donc irréversible.

Cela tient à trois raisons. Tout d’abord, la Grande-Bretagne et les Puissances alliées exercent une autorité légitime et absolue sur la Palestine au moment où elles prennent ces décisions. Par droit de conquête, ce qui est alors suffisant en soi, et par traité, la Turquie ayant renoncé à ce territoire à trois reprises : un armistice signé en 1918, le traité de Sèvres de 1920, et enfin le traité de Lausanne de 1923, qui se substitue au précédent. Certes, le texte de Lausanne n’a été formellement signé qu’en juillet 1923, après la promulgation du Mandat ; mais le gouvernement turc a fait savoir dès 1922 qu’il ne contestait celui de Sèvres qu’à propos de l’Anatolie, et acceptait au contraire ses dispositions sur les autres territoires qui relevaient jusqu’en 1914 de l’Empire ottoman, à commencer par le Levant.

Ensuite, la Puissance ou le groupe de Puissances qui contrôle légitimement un territoire en dispose à sa guise. Ce principe ne fait l’objet d’aucune restriction avant et pendant la Première Guerre mondiale. A partir du traité de Versailles, en 1919, son application est tempérée par un autre principe, l’autodétermination des populations. Mais il reste en vigueur pour l’essentiel : l’autodétermination étant tenue pour souhaitable a priori, mais ne revêtant jamais de caractère obligatoire, et pouvant même être refusée (ce sera le cas de l’Autriche germanophone, à laquelle le traité de Versailles interdit, dès 1919, de s’unir à l’Allemagne). La Grande-Bretagne, les Puissances alliées et la SDN sont donc juridiquement en mesure de créer n’importe quelle entité dans les territoires dont la Turquie s’est dessaisie et l’attribuer à n’importe quel seigneur ou groupe humain. Ce qu’elles font, en établissant plusieurs Etats arabes (Syrie puis Liban, Irak, Transjordanie) et un Etat juif (la Palestine) ; en installant à la tête de certains de ces Etats des souverains (Fayçal en Irak, Abdallah en Transjordanie) ou en réservant d’autres, de manière implicite ou explicite, à une communauté ethnico-religieuse particulière (les chrétiens au Liban, les druzes et les alaouites dans certaines régions de la Syrie, les Juifs en Palestine) ; en renonçant à créer un Etat arménien en Anatolie orientale, ou un Etat kurde aux confins de l’Anatolie et de la Mésopotamie ; en contraignant de manière arbitraire plusieurs ethnies et communautés à vivre au sein d’un même Etat en Irak

Enfin, une Puissance ou un groupe de Puissances peut disposer d’un territoire de deux façons : en lui refusant toute personnalité propre, à travers une annexion ou un statut de dépendance complète ; ou en la lui accordant. Dans le premier cas, elle peut lui imposer successivement, et pour ainsi dire à l’infini, les statuts les plus divers. Dans le second, elle ne peut revenir sur le statut initialement accordé. Les territoires non-européens conquis par les Alliés de la Première Guerre mondiale entrent tous dans cette dernière catégorie : qu’il s’agisse des colonies et dépendances allemandes d’Afrique et du Pacifique ou des possessions levantines, mésopotamiennes et arabiques de l’Empire ottoman. Ils ont tous été érigés en « territoires mandataires », dotés d’une personnalité et ayant vocation à l’indépendance en fonction de leur « niveau de développement ».

Un mandat est un instrument par lequel une personne (le mandant) en charge une autre (le mandataire) d’exécuter une action. Par extension, ce peut être également un instrument par lequel une personne majeure, tutrice légale d’une personne mineure, charge une autre personne majeure d’exécuter une action au profit de sa pupille. C’est exactement la situation que décrit la Charte de la SDN quand elle crée des « territoires mandataires »dans le cadre du traité de Versailles. L’article XXII de la Charte déclare : « Aux colonies et territoires qui, par suite de la guerre, ne sont plus sous la souveraineté des Etats qui les gouvernaient dans le passé et dont la population n’est pas encore capable de se gouverner elle-même, on appliquera le principe selon lequel le bien-être et le développement de ladite civilisation constitue une mission civilisatrice sacrée… La meilleure méthode pour accomplir cette mission sera de confier la tutelle de ces populations à des nations plus avancées… » Il distingue ensuite entre des territoires mandataires susceptibles d’accéder rapidement à une existence indépendante (qui seront qualifiés par la suite de « mandats de la classe A »), d’autres où celle-ci ne pourra être assurée que dans un avenir plus lointain (« classe B ») et quelques-uns, enfin, qui pour telle ou telle autre raison, notamment l’absence d’une population substantielle, pourront être administrés, en pratique, comme une partie intégrante du territoire de la puissance mandataire (« classe C »).

La Palestine, comme tous les territoires précédemment ottomans, fait partie de la classe A. Le texte même du Mandat ne laisse aucune ambiguïté sur la population en faveur de laquelle la tutelle est organisée en termes politiques et qui doit donc disposer, à terme, d’un Etat indépendant : il s’agit exclusivement du peuple juif ((articles II, IV, VI, VII, XI, XXII, XXIII), même si les droits civils des autres populations ou communautés, arabophones pour la plupart, sont expressément garantis.

Cette décision n’a rien d’arbitraire ou d’injuste, dans la mesure ou d’autres Mandats sont établis au même moment en faveur de populations arabes du Levant et de Mésopotamie, sur des territoires plus étendus. Mais même si elle était arbitraire ou injuste, ou si la population non-juive n’était pas consultée ni autorisée à faire valoir son droit à l’autodétermination, elle n’en serait pas moins parfaitement conforme au droit. Comme la Cour internationale de justice devait le réaffirmer sans cesse par la suite, notamment une cinquantaine d’années plus tard, en 1975, à propos du Sahara Occidental, dont l’Espagne entendait se dessaisir au profit du Maroc et de la Mauritanie, sans consulter la population locale : « La validité du principe d’autodétermination, définie comme la nécessité de prendre en considération la volonté librement exprimée des peuples, n’est nullement affectée par le fait que dans certains cas l’autorité internationale a dispensé d’organiser une telle consultation auprès des habitants d’un territoire donné. Ces décisions ont été fondées soit sur la considération que la population en question ne constituait pas ‘un peuple’ jouissant du droit à l’autodétermination, soit sur la conviction qu’une consultation n’était pas nécessaire compte tenu de certaines circonstances ».

Une fois la Palestine dotée d’une personnalité en droit international public et érigée en Foyer national juif, personne, ni la puissance tutélaire britannique, ni les Puissances en général, ni la SDN en particulier, ni l’ONU en tant qu’héritière et successeur de la SDN depuis 1945, ne peut la dépouiller de ces caractères. C’est une application du principe le plus ancien et le plus fondamental du droit international public : les traités lient absolument et irrévocablement les Etats qui les concluent, et ont priorité sur leurs lois internes. Ou pour reprendre l’adage latin : pacta sunt servanda (« Il est dans la nature des traités d’être intégralement exécutés »). C’est aussi la conséquence de l’article 80 de la Charte des Nations Unies, qui stipule que les dispositions concernant les pays sous tutelle internationale ne peuvent être modifiées. Seul le bénéficiaire du Mandat – le peuple juif – peut librement et volontairement renoncer à ce qui lui a été octroyé.

(Il convient de noter, accessoirement, que la légalité ontologique des traités et décisions souveraines créant des Etats ou fixant leurs frontières, en dehors de toute considération logique ou éthique, s’applique à toutes les entités de droit international. La plupart des Etats actuels de l’Europe centrale et balkanique ont été créés arbitrairement et non sans diverses injustices par le traité de Versailles de 1919, puis modifiés, non moins arbitrairement et en vertu d’une justice non moins relative, par les vainqueurs de 1945 ; la quasi-totalité des Etats actuels du Proche et du Moyen-Orient, d’Asie du Sud, d’Asie du Sud-Est, d’Afrique et d’Océanie ont été façonnés arbitrairement et souvent de manière injuste par les puissances occidentales dans le cadre du système colonial qui a prévalu jusqu’aux années 1940-1970. Pour autant, l’existence de ces Etats et la permanence de ces frontières sont tenues pour intangibles.)

De fait, la politique réellement menée par les Britanniques en Palestine dès 1923 et jusqu’en 1947 semble bien avoir eu pour objet d’amener les instances représentatives du peuple juif en général, à commencer par l’Organisation sioniste mondiale, et du peuple juif palestinien en particulier, à renoncer volontairement à leurs droits sur la Palestine. Et elle a été largement couronnée de succès : ces instances ayant accepté ou toléré successivement l’amputation de la Palestine orientale ou transjordanienne, en 1923, les restrictions diverses apportées à l’immigration juive, des projets de « partition »de la Palestine occidentale, entre Méditerranée et Jourdain – Plan Peel de 1937, Plan Woodhead de 1938 -, l’indépendance de la Transjordanie en 1946. Sans l’inique Livre Blanc de 1939, qui ne prétendait plus aménager le Mandat avec le concours plus ou moins forcé et contraint des Juifs, mais l’abolir, les Juifs palestiniens n’auraient pas probablement engagé, dès 1939 pour les uns, à partir de 1945 pour les autres, une action politique et militaire en vue de la transformation de la Palestine mandataire en Etat juif souverain

Cette action politique et militaire amène la Grande-Bretagne à renoncer le 2 avril 1947 au mandat sur la Palestine. Le 29 novembre 1947, les instances représentatives juives acceptent un plan de partage de la Palestine occidentale en trois entités – Etat juif, Etat arabe et zone internationale provisoire (corpus separatus) de Jérusalem – élaboré par une commission de l’ONU, et ratifiée par l’Assemblée générale de cette organisation. Si les instances représentatives arabes de Palestine et les pays de la Ligue arabe avaient également donné leur accord, les droits des Juifs à l’ensemble d’un territoire de Palestine, tels qu’ils avaient été énoncés par les actes internationaux de 1920 et 1922, auraient été définitivement restreints au seul Etat juif ainsi défini et dans une moindre mesure à Jérusalem.

Mais ni les instances arabes palestiniennes ni les pays de la Ligue arabe n’ont accepté le plan de l’ONU. Or le droit international public prévoit une telle situation : la nature d’un traité étant d’être exécuté, un traité qui ne l’est pas, par suite du retrait ou de la défaillance de l’une des parties concernées, est réputé nul et non avenu, et la situation juridique antérieure, statu quo ante, est reconduite. Comme le note dans un télégramme au Quai d’Orsay un diplomate français en poste à Jérusalem pendant la guerre de 1947-1948, les dispositions du Mandat de 1923 redeviennent donc « la loi du pays ». Elles « s’accomplissent » immédiatementen Israël, tant dans le territoire attribué aux Juifs par le plan de partage de 1947 que dans les secteurs conquis en 1948 sur ce qui aurait pu être constitué en Etat arabe ou en zone internationale de Jérusalem : puisque le nouvel Etat est établi au profit et dans l’intérêt du peuple juif, conformément au Mandat, notamment en matière d’immigration. Elles restent en vigueur, bien qu’ « inaccomplies » et suspendues sine die, dans les zones qui passent sous le contrôle d’Etats arabes : la plus grande partie de la Cisjordanie et les secteurs nord, est et sud de Jérusalem, occupés par les Transjordaniens (qui prennent à cette occasion le nouveau nom de Jordaniens) ; et la bande de Gaza, occupée par l’Egypte.

(Il existe, sur ce point, une jurisprudence de la Cour internationale de justice (ICJ) : l’opinion, rendue en 1950, sur le Sud-Ouest Africain – la Namibie actuelle -, colonie allemande devenue mandat de catégorie C à l’issue de la Première Guerre mondiale, que l’Afrique du Sud entendait annexer. La Cour internationale avait estimé à cette occasion qu’un mandat de la SDN, sans acception de catégorie, ne pouvait être éteint que par la réalisation de son objet premier, quel qu’il soit, même si les conditions géopolitiques s’étaient modifiées.)

En 1949, Israël signe des cessez-le-feu avec tous ses voisins. Ces accords doivent être suivis de traités de paix. Mais le chef d’Etat arabe le plus disposé à une telle évolution, le roi Abdallah de Jordanie, est assassiné dès 1951. Ses successeurs – son fils Talal, puis le Conseil de Régence qui prend le pouvoir en 1952 – interrompent les négociations. En Egypte, le régime fascisant instauré par Gamal Abd-el-Nasser en 1953 rejette toute normalisation avec Israël. Les autres pays arabes se raidissent à leur tour. Ce n’est qu’en 1979, trente ans après les cessez-le-feu de Rhodes, dix ans après la mort de Nasser, et après plusieurs autres guerres majeures, qu’un premier traité de paix israélo-arabe sera enfin signé à Washington : entre Israël et l’Egypte. Un second traité, avec la Jordanie, sera signé en 1994, quarante-cinq ans après Rhodes.

La logique de 1947 s’applique à 1979. Si des traités de paix avaient confirmé les cessez-le-feu, dès les années 1950, et transformé les lignes d’armistice (la « ligne verte ») en frontière internationale, les dispositions du Mandat de 1923, un moment ranimées du fait de la non-application du plan de partage, se seraient définitivement éteintes en Cisjordanie, dans le secteur de jordanien de Jérusalem, et à Gaza ; Israël n’aurait pu exercer par la suite la moindre revendication sur ces territoires. Mais en l’absence de traité, l’Etat juif garde ses prérogatives. Ce que révèle brusquement la guerre des Six Jours qui, en 1967, lui livre les trois territoires contestés, ainsi le Golan syrien et le Sinaï égyptien : tout en se conformant, en pratique et pour l’essentiel, aux obligations d’une « puissance occupante », telles qu’elles sont définies par les conventions de Genève, les Israéliens rappellent qu’ils détiennent des droits éminents sur toute l’ancienne Palestine mandataire. Ils s’en autorisent pour réunifier Jérusalem sous leur autorité, mais aussi pour « implanter » des localités civiles israéliennes en Cisjordanie et à Gaza. Sous un régime de simple occupation militaire, cela pourrait constituer une violation de la IVe Convention de Genève. Compte tenu du statut juridique originel de la Palestine, c’est au contraire un acte légitime. Même s’il peut être considéré, politiquement ou géopolitiquement, pour inopportun.

De nombreux juristes de premier plan souscrivent à cette analyse : notamment l’Américain Eugene Rostow, ancien doyen de la faculté de droit de Yale, et ancien sous-secrétaire d’Etat sous l’administration Johnson, et l’Australien Julius Stone, l’un des plus grands experts en droit international du XXe siècle. Cela amène les pays où le droit en soi joue un rôle dans le débat politique, notamment les Etats-Unis, à reconnaître explicitement les droits éminents du peuple juf sur l’ancienne Palestine mandataire – le Congrès américain votera en 1995, sous l’administration Clinton, une loi enjoignant l’installation de l’ambassade américaine en Israël à Jérusalem – , ou du moins réserver leur opinion, en parlant de « territoires contestés » (disputed areas) plutôt que de « territoires occupés » (occupied areas). Cela empêche, par ailleurs, le vote d’éventuelles sanctions contre Israël, dans des organisations internationales où les ennemis de l’Etat juif – pays arabes ou musulmans, Etats communistes jusqu’au début des années 1990, et pays dits « non-alignés »– disposent pourtant de « majorités automatiques ».

Pour autant, les Israéliens ont longtemps hésité à faire de leurs droits éminents le cœur de leur argumentation diplomatique sur la question des territoires conquis en 1967.

Leur principale motivation, à cet égard, a longtemps relevé de la politique intérieure. Cette question a servi jusqu’aux accords d’Oslo de 1993, voire même jusqu’au retrait de Gaza en 2005, de démarcation symbolique entre une droite populiste ou religieuse, décidée à les conserver, et une gauche élitiste et laïque, prête à les céder en échange de la paix : si bien que les hommes politiques, diplomates et juristes de gauche ou du centre-gauche ont redouté, en insistant sur la notion de droits éminents, de faire le jeu de leurs adversaires de droite ou du centre-droit.

Une seconde motivation était d’ordre technique : les Israéliens ont jugé plus simple d’exciper, pour l’ancien secteur jordanien de Jérusalem, de la Cisjordanie et de Gaza, d’un statut de territoire au statut indéterminé. En effet, l’annexion des deux premiers territoires à la Jordanie n’a jamais été reconnue en droit international entre 1949 et 1967 ; et le troisième territoire, Gaza, a été placée pendant la même période sous une simple administration égyptienne. Mais en fait cette doctrine subsidiaire renvoie implicitement aux droits éminents, Israël faisant valoir sur ces territoires, outre son droit incontestable d’ « occupant belligérant » à la suite de la guerre de 1967, des « droits antérieurs » sur l’ensemble de la Palestine mandataire.

En janvier 2012, le gouvernement israélien a demandé à une commission spéciale d’examiner le statut juridique de la Cisjordanie et des localités juives qui y ont été créées depuis le cessez-le-feu de 1967. Connue sous le nom de Commission Lévy du nom de son président, Edmund Lévy, ancien juge à la Cour suprême d’Israël, celle-ci a retenu explicitement, dans un rapport daté du 21 juin 2012 et rendu public le 9 juillet de la même année, la doctrine des droits éminents de l’Etat hébreu sur la Cisjordanie, et donc de la légalité absolue de ses localités juives. Le document a été ensuite examiné et approuvé par le Bureau du Conseiller juridique du Gouvernement, un organisme comparable, par ses attributions et son autorité, au Conseil d’Etat français.

En apportant son soutien à la résolution UNSC 2334, le président Obama donne à son successeur, le président Trump, l’opportunité de redéfinir clairement la doctrine diplomatique américaine sur la Palestine. Et d’exiger sans détours le respect du droit.

© Michel Gurfinkiel, 2016

Annexe :

Le Statut des Territoires de Judée et de Samarie (ou Cisjordanie) selon le droit international

(Rapport de la Commission Lévy, 21 juin 2012)

The Status of the Territories of Judea and Samaria according to International Law (As defined by the Levy Commission Report, 21 June 2012)

In light of the different approaches in regard to the status of the State of Israel and its activities in Judea and Samaria, any examination of the issue of land and settlement thereon requires, first and foremost, clarification of the issue of the status of the territory according to international law.

Some take the view that the answer to the issue of settlements is a simple one inasmuch as it is prohibited according to international law. That is the view of Peace Now (see the letter from Hagit Ofran from 2 April 2010); B’tselem (see the letter from its Executive Director Jessica Montell from 29 March 2012, and its pamphlet Land Grab: Israel’s Settlement Policy in the West Bank, published May 2002); Yesh Din and the Association for Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI) (see the letter from Attorney Tamar Feldman from 19 April 2012); and Adalah (see the letter from attorney Fatma Alaju from 12 June 2012).

The approach taken by these organizations is a reflection of the position taken by the Palestinian leadership and some in the international community, who view Israel’s status as that of a “military occupier,” and the settlement endeavor as an entirely illegal phenomenon. This approach denies any Israeli or Jewish right to these territories. To sum up, they claim that the territories of Judea and Samaria are “occupied territory” as defined by international law in that they were captured from the Kingdom of Jordan in 1967. Consequently, according to this approach, the provisions of international law regarding the matter of occupation apply to Israel as a military occupier, i.e. Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land. The Hague, 18 October 1907,1 which govern the relationship between the occupier the occupied territory, and the Fourth Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. Geneva, 12 August (1949).2

According to the Hague Regulations, the occupying power, while concerning himself with the occupier’s security needs, is required to care for the needs of the civilian population until the occupation is terminated. According to these regulations, it is forbidden in principle to seize personal property, although the occupying power has the right to enjoy all the advantages derivable from the use of the property of the occupied state, and public property that is not privately owned without changing its fixed nature. Moreover, according to this approach, Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention prohibits the transfer of parts of the occupying power’s own civilian population into the territory it occupies.3 Accordingly, in their view, the establishment of settlements carried out by Israel is in violation of this article, even without addressing the type or status of the land upon which they are built.

In this context, we were presented with an approach by some of the abovementioned organizations, whereby they do not accept the premise that the lands that do not constitute personal property are state lands. It was claimed that in the absence of orderly registration of most of the land in Judea and Samaria, and precise registration of the rights of the local inhabitants, it is reasonable to assume that the local population is entitled to benefit from land that is neither defined nor registered as privately owned land. From this it follows that the use of land for the purpose of the establishment of Israeli settlements impinges on the rights of the local population, which is a protected population according to the Convention, and Israel, as an occupying power, is obliged to safeguard these rights and not deny them by exploiting the land for the benefit of its own population.4

If this legal approach were correct, we would, in accordance with our Terms of reference, be required to terminate the work of this Committee, since in such circumstances, we could not recommend regularizing the status of the settlements. On the contrary, we would be required to recommend that the proper authorities remove them.

However, we were also presented with another legal position, inter alia by the Regavim movement (Attorneys Bezalel Smotritz and Amit Fisher) and by the Benjamin Regional Council (the expert legal opinion of Attorneys Daniel Reisner and Harel Arnon). They are of the view that Israel is not an “Occupying Power” as determined by international law inter alia because the territories of Judea and Samaria were never a legitimate part of any Arab state, including the kingdom of Jordan. Consequently, those conventions dealing with the administration of occupied territory and an occupied populations are not applicable to Israel’s presence in Judea and Samaria.

According to this approach, even if the Geneva Convention applied, Article 49 was never intended to apply to the circumstances of Israel’s settlements. Article 49 was drafted by the Allies after World War II to prevent the forcible transfer of an occupied population, as was carried out by Nazi Germany, which forcibly transferred people from Germany to Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia with the aim of changing the demographic and cultural makeup of the population. These circumstances do not exist in the case of Israel’s settlement. Other than the fundamental commitment that applies universally by virtue of international humanitarian norms to respect individual personal property rights and uphold the law that applied in the territory prior to the IDF entering it, there is no fundamental restriction to Israel’s right to utilize the land and allow its citizens to settle there, as long as the property rights of the local inhabitants are not harmed and as long as no decision to the contrary is made by the government of Israel in the context of regional peace negotiations.

Is Israel’s status that of a “military occupier” with all that this implies in accordance with international law? In our view, the answer to this question is no.

After having considered all the approaches placed before us, the most reasonable interpretation of those provisions of international law appears to be that the accepted term “occupier” with its attending obligations, is intended to apply to brief periods of the occupation of the territory of a sovereign state pending termination of the conflict between the parties and the return of the territory or any other agreed upon arrangement. However, Israel’s presence in Judea and Samaria is fundamentally different: Its control of the territory spans decades and no one can foresee when or if it will end; the territory was captured from a state (the kingdom of Jordan), whose sovereignty over the territory had never been legally and definitively affirmed, and has since renounced its claim of sovereignty; the State of Israel has a claim to sovereign right over the territory.

As for Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, many have offered interpretations, and the predominant view appears to be that that article was indeed intended to address the harsh reality dictated by certain countries during World War II when portions of their populations were forcibly deported and transferred into the territories they seized, a process that was accompanied by a substantial worsening of the status of the occupied population (see HCJ 785/87 Affo et al. v. Commander of IDF Forces in the West Bank et al. IsrSC 42(2) 1; and the article by Alan Baker: “The Settlements Issue: Distorting the Geneva Conventions and Oslo Accords, from January 2011.5)

This interpretation is supported by several sources: The authoritative interpretation of the International Committee of the Red Cross (IRCC), the body entrusted with the implementation of the Fourth Geneva Convention,6 in which the purpose of Article 49 is stated as follows:

“It is intended to prevent a practice adopted during the Second World War by certain Powers, which transferred portions of their own population to occupied territory for political and racial reasons or in order, as they claimed, to colonize those territories. Such transfers worsened the economic situation of the native population and endangered their separate existence as a race.”

Legal scholars Prof. Eugene Rostow, Dean of Yale Law School in the US, and Prof. Julius Stone have acknowledged that Article 49 was intended to prevent the inhumane atrocities carried out by the Nazis, e.g. the massive transfer of people into conquered territory for the purpose of extermination, slave labor or colonization:7 8

“The Convention prohibits many of the inhumane practices of the Nazis and the Soviet Union during and before the Second World War – the mass transfer of people into and out of occupied territories for purposes of extermination, slave labor or colonization, for example….The Jewish settlers in the West Bank are most emphatically volunteers. They have not been “deported” or “transferred” to the area by the Government of Israel, and their movement involves none of the atrocious purposes or harmful effects on the existing population it is the goal of the Geneva Convention to prevent.”(Rostow)

“Irony would…be pushed to the absurdity of claiming that Article 49(6) designed to prevent repetition of Nazi-type genocidal policies of rendering Nazi metropolitan territories judenrein, has now come to mean that…the West Bank…must be made judenrein and must be so maintained, if necessary by the use of force by the government of Israel against its own inhabitants. Common sense as well as correct historical and functional context excludes so tyrannical a reading of Article 49(6.).” (Julius Stone)

We are not convinced that an analogy may be drawn between this legal provision and those who sought to settle in Judea and Samaria, who were neither forcibly “deported” nor “transferred,” but who rather chose to live there based on their ideology of settling the Land of Israel.

We have not lost sight of the views of those who believe that the Fourth Geneva Convention should be interpreted so as also to prohibit the occupying state from encouraging or supporting the transfer of parts of its population to the occupied territory, even if it did not initiate it.9 However, even if this interpretation is correct, we would not alter our conclusions that Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention does not apply to Jewish settlement in Judea and Samaria in view of the status of the territory according to international law. On this matter, we offer a brief historical review.

On 2 November 1917 –17 Heshvan 5678, Lord James Balfour, the British Foreign Secretary, published a declaration saying that:

“His Majesty’s Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.10 ’’

In this declaration, Britain acknowledged the rights of the Jewish people in the Land of Israel and expressed its willingness to promote a process that would ultimately lead to the establishment of a national home for it in this part of the world. This declaration reappeared in a different form, in the resolution of the Peace Conference in San Remo, Italy, which laid the foundations for the British Mandate over the Land of Israel and recognized the historical bond between the Jewish people and Palestine (see the preamble):

“The principal Allied powers have also agreed that the Mandatory should be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 2nd, 1917, by the Government of His Britannic Majesty, and adopted by the said powers, in favor of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, it being clearly understood that nothing should be done which might prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country. […] Recognition has thereby been given to the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine and to the grounds for reconstituting their national home in that country.”11

It should be noted here that the mandatory instrument (like the Balfour Declaration) noted only that “the civil and religious rights” of the inhabitants of Palestine should be protected, and no mention was made of the realization of the national rights of the Arab nation. As for the practical implementation of this declaration, Article 2 of the Mandatory Instrument states:12

“The Mandatory shall be responsible for placing the country under such political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home, as laid down in the preamble, and the development of self-governing institutions, and also for safeguarding the civil and religious rights of all the inhabitants of Palestine, irrespective of race and religion.”

And Article 6 of the Palestine Mandate states:

“The Administration of Palestine, while ensuring that the rights and position of other sections of the population are not prejudiced, shall facilitate Jewish immigration under suitable conditions and shall encourage, in co-operation with the Jewish agency referred to in Article 4, close settlement by Jews on the land, including State lands and waste lands not required for public purposes.”

In August 1922 the League of Nations approved the mandate given to Britain, thereby recognizing, as a norm enshrined in international law, the right of the Jewish people to determine its home in the Land of Israel, its historic homeland, and establish its state therein.

To complete the picture, we would add that upon the establishment of the United Nations in 1945, Article 80 of its Charter determined the principle of recognition of the continued validity of existing rights of states and nations acquired pursuant to various mandates, including of course the right of the Jews to settle in the Land of Israel, as specified in the abovementioned documents:

‘Except as may be agreed upon in individual trusteeship agreements […] nothing in this Chapter shall be construed in or of itself to alter in any manner the rights whatsoever of any states or any peoples or the terms of existing international instruments to which Members of the United Nations may respectively be parties” (Article 80, Paragraph 1, UN Charter).

In November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the recommendations of the committee it had established regarding the partition of the Land of Israel west of the Jordan into two states.13 However, this plan was never carried out and accordingly did not secure a foothold in international law after the Arab states rejected it and launched a war to prevent both its implementation and the establishment of a Jewish state. The results of that war determined the political reality that followed: The Jewish state was established within the territory that was acquired in the war. On the other hand, the Arab state was not formed, and Egypt and Jordan controlled the territories they captured (Gaza, Judea and Samaria). Later,

the Arab countries, which refused to accept the outcome of the war, insisted that the Armistice Agreement include a declaration that under no circumstances should the armistice demarcation lines be regarded as a political or territorial border.14 Despite this, in April 1950, Jordan annexed the territories of Judea and Samaria,15 unlike Egypt, which did not demand sovereignty over the Gaza Strip. However, Jordan’s annexation did not attain legal standing and was opposed even by the majority of Arab countries, until in 1988, Jordan declared that it no longer considered itself as having any status over that area (on this matter see Supreme Court President Landau’s remarks in HCJ 61/80 Haetzni v. State of Israel, IsrSC 34(3) 595, 597; HCJ 69/81 Bassil Abu Aita et al. v. The Regional Commander of Judea and Samaria et al., IsrSC 37(2) 197, 227).

This restored the legal status of the territory to its original status, i.e. territory designated to serve as the national home of the Jewish people, which retained its “right of possession” during the period of the Jordanian control, but was absent from the area for a number of years due to the war that was forced on it, but has since returned.

Alongside its international commitment to administer the territory and care for the rights of the local population and public order, Israel has had every right to claim sovereignty over these territories, as maintained by all Israeli governments. Despite this, they opted not to annex the territory, but rather to adopt a pragmatic approach in order to enable peace negotiations with the representatives of the Palestinian people and the Arab states. Thus, Israel has never viewed itself as an occupying power in the classic sense of the term, and subsequently, has never taken upon itself to apply the Fourth Geneva Convention to the territories of Judea, Samaria and Gaza. At this point, it should be noted that the government of Israel did indeed ratify the Convention in 1951, although it was never made part of Israeli law by way of Knesset legislation (on this matter, see CrimA 131/67 Kamiar v. State of Israel, 22 (2) IsrSC 85, 97; HCJ 393/82 Jam’iat Iscan Al-Ma’almoun v. Commander of the IDF Forces in the Area of Judea and Samaria, IsrSC 37(4) 785).

Israel voluntarily chose to uphold the humanitarian provisions of the Convention (HCJ 337/71, Christian Society for the Holy Places v. Minister of Defense, IsrSC 26(1) 574; HCJ 256/72, Electricity Company for Jerusalem District v. Minister of Defense et al., IsrSC 27(1) 124; HCJ 698/80 Kawasme et al. v. The Minister of Defense et al., IsrSC 35(1) 617; HCJ 1661/05 Hof Aza. Regional Council et al. v. Knesset of Israel et al., IsrSC 59(2) 481).

As a result, Israel pursued a policy that allowed Israelis to voluntarily establish their residence in the territory in accordance with the rules determined by the Israeli government and under the supervision of the Israeli legal system, subject to the fact that their continued presence would be subject to the outcome of the diplomatic negotiations.

In view of the above, we have no doubt that from the perspective of international law, the establishment of Jewish settlements in Judea and Samaria is not illegal.

- 1 Convention (IV) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its annex: Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land. The Hague, 18 October 1907.

- 2 http://www.icrc.org/ihl.nsf/INTRO/380

- 3 Individual or mass forcible transfers, as well as deportations of protected persons from occupied territory to the territory of the Occupying Power or to that of any other country, occupied or not, are prohibited, regardless of their motive. Nevertheless, the Occupying Power may undertake total or partial evacuation of a given area if the security of the population or imperative military reasons does demand. Such evacuations may not involve the displacement of protected persons outside the bounds of the occupied territory except when for material reasons it is impossible to avoid such displacement. Persons thus evacuated shall be transferred back to their homes as soon as hostilities in the area in question have ceased. The Occupying Power undertaking such transfers or evacuations shall ensure, to the greatest practicable extent, that proper accommodation is provided to receive the protected persons, that the removals are effected in satisfactory conditions of hygiene, health, safety and nutrition, and that members of the same family are not separated. The Protecting Power shall be informed of any transfers and evacuations as soon as they have taken place. The Occupying Power shall not detain protected persons in an area particularly exposed to the dangers of war unless the security of the population or imperative military reasons so demands. The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.

- 4 The position of Peace Now. See also B’tselem: Under the Guise Of Legality: Israel’s Declarations of State Land in the West Bank, February 2012.

- 5 http://jcpa.org/article/the-settlements-issue-distorting-the-geneva-convention-and-the-oslo-accords/